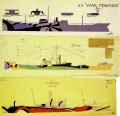

During World War I, the British and Americans faced a serious threat from German U-boats, which were sinking allied shipping at a dangerous rate. All attempts to camouflage ships at sea had failed, as the appearance of the sea and sky are always changing. Any color scheme that was concealing in one situation was conspicuous in others. A British artist and naval officer, Norman Wilkinson, promoted a new camouflage scheme. Instead of trying to conceal the ship, it simply broke up its lines and made it more difficult for the U-boat captain to determine the ship's course. The British called this camouflage scheme "Dazzle Painting." The Americans called it "Razzle Dazzle."

UPDATE: Most references report that dazzle painting designs were derived from the artistic fashions of the time, particularly cubism. I have recently (2009) received conflicting information from Colin Biddle, who wrote his thesis on dazzle painting. He says that " ... there is no connection to cubism nor to abstract artistic movements of the time such as Futurism and Vorticism. It was purely an idea of Wilkinson's ... Only after many trials of differing patterns and combination of colours did the Royal Navy go ahead with the dazzle idea. Much poor reportage has been forthcoming on this assuming that the art movement of the time was responsible. This is the myth." Mr. Biddle's thesis is available in the library of Hereford College of Arts, Hereford, Herefordshire, UK, 2008.